Sara Knowland

Painter Sara Knowland is rigorous about her medium. Yes: she occupies herself with the formal qualities of paint and the perceptual experiences her compositions conjure. But she is also fixated on the medium of her eye as the surface par excellence that transforms external realities into felt experiences. In Hot Heeled and Glancing, her solo exhibition on view at Carlye Packer, Knowland works with source imagery pulled from references as various as Northern Renaissance painting, avant-garde performance art, and ’80s horror (and its 2010s remakes) to reflect on contemporary ways of seeing and feeling the world.

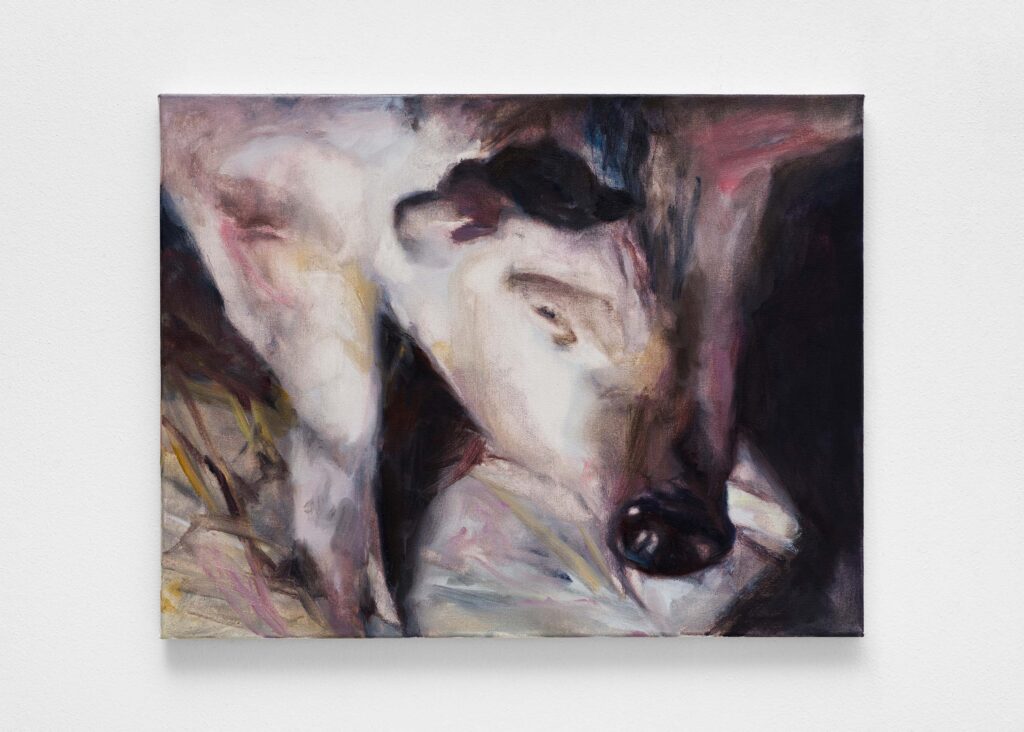

Milk, 2022

The title of your exhibition, Hot Heeled and Glancing, evokes suspicion and urgency. While encountering the exhibition in person, I was attuned both to an overarching atmosphere of danger and to the ways you experiment with temporality and speed—particularly formally, with your propulsive brushstrokes.

“Hot Heeled and Glancing” is a phrase that I had in my head, which I know I read somewhere last year—I think it might have been from Anne Carson, but I’m not one hundred percent sure. I tried to track down its origin, but eventually, I felt like it might not really matter. It’s just cool that it’s been lingering in my mind for so long.

The first part of the phrase, “hot heeled,” brings up ideas about the female that feels appropriate to my work and to my research in the representation of the female within cinema. The second speaks to a certain kind of looking that interests me: when you “glance,” you are seeing something in your periphery, rather than focusing on the main image within your field of vision.

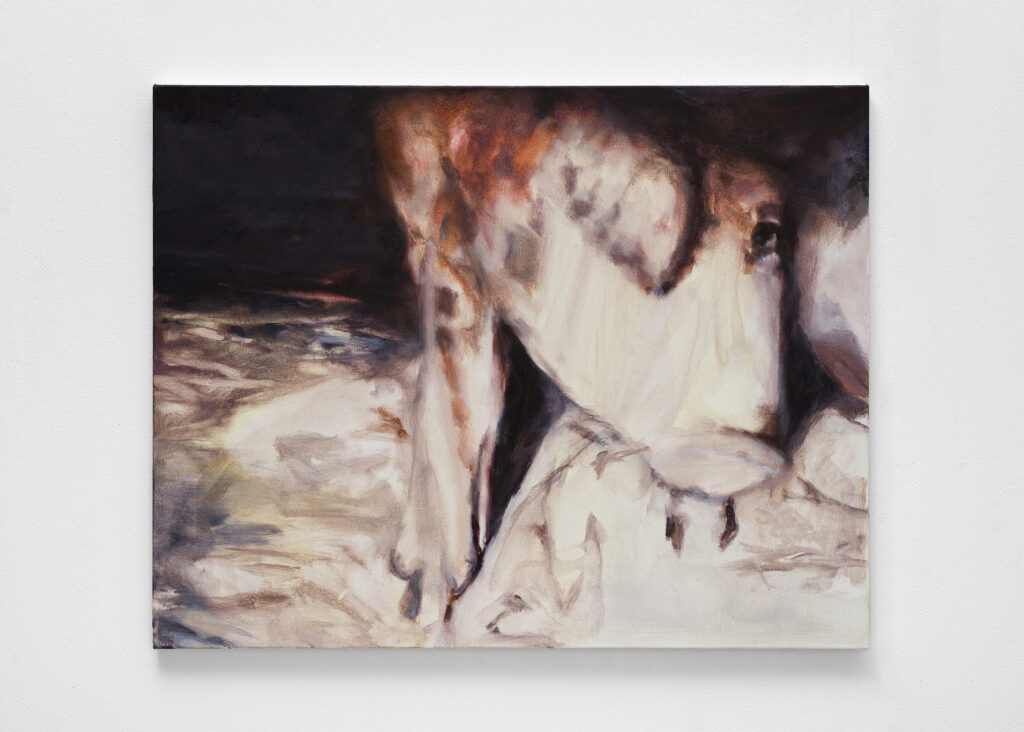

Policed sows ii, 2022

“Hot heeled” suggests a kind of aggression within the feminine that crops up throughout your work. Your painting Milk depicts a hunched and growling dog squaring up to a single, delicate egg resting on someone’s palm. The egg is this fragile piece of potential life but nevertheless instills fear in the dog.

While making that painting, I had been reading Caliban and the Witch by Sylvia Federici, which is about the history of witch hunts and details the murder of thousands of women at a point when the commons were being reorganized as capitalism superseded feudalism. There is a moment when she describes the medieval imagery of the witch, and how a specific culture of animals—cats, dogs, hares—accompanied the witch in those depictions.

I was also thinking of motherhood while working on the painting and wanted to make the river very opaque and milky. There are obvious associations that come with women and water: tides, the moon, et cetera. I tend to work in a way where there are political concerns, but these things are underlying in the paintings rather than absolutely on their surfaces.

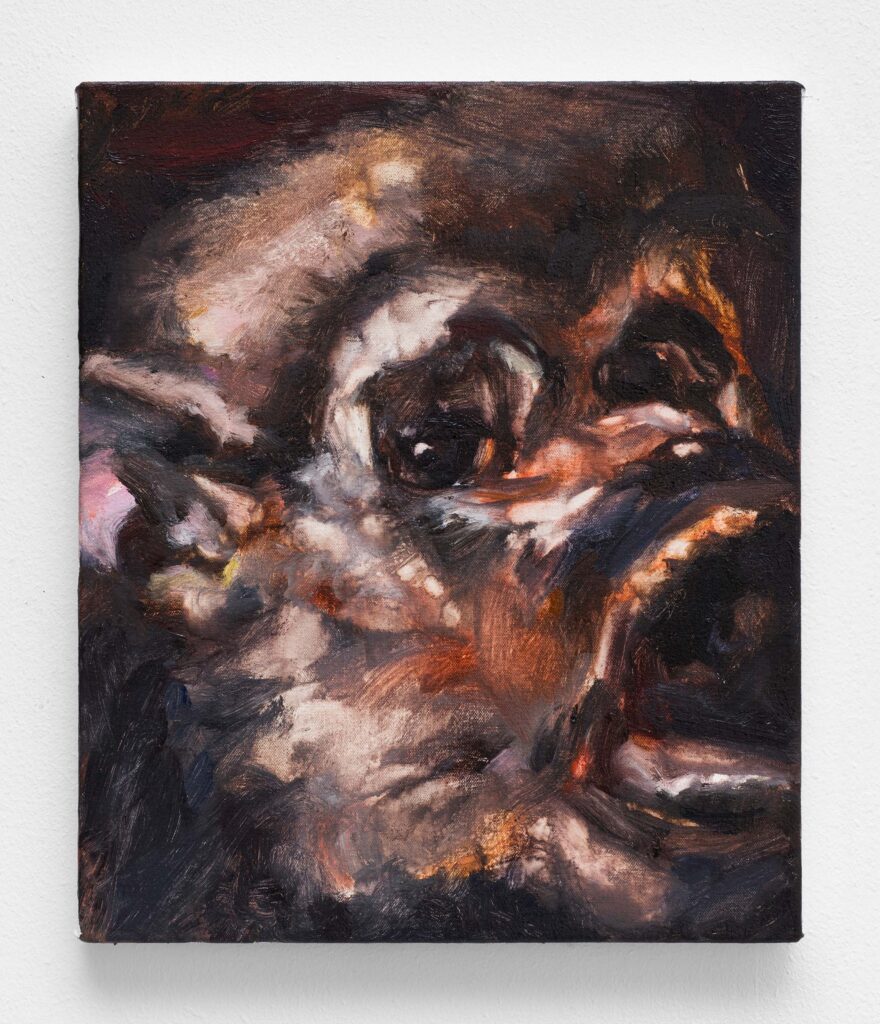

Policed sow verso ii, 2022

Tell me more about your sow paintings, wherein you depict pigs—often at a high angle—in gauzy chiaroscuro.

I was thinking about the visual language of policing, which manifests in the works as a flashlight beam shining at the sows’ faces. I started making the sow paintings probably about a year after the murder of a young woman named Sarah Everard, who was killed by an off-duty cop. During her vigil, which was held while the lockdown was still instated, the police behaved quite brutally, breaking apart the vigil and sort of attacking people who had been standing there with candles. As a slang word, we call cops pigs, and yet the pigs in my paintings are the subjects being policed, in a way—so it was a potent image to work with.

I was also reading Barbara Creed’s The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, and Psychoanalysis, wherein she describes how blood in horror denotes the menstrual, making body horror at large tied to anxieties about femininity. I was thinking about the scene in the 2013 Carrie directed by Kimberly Peirce, in which the high schoolers slaughter a pig, collect its blood, and pour it over Carrie as she becomes prom queen. At first, I started working with images I took on my phone of the screen, but that shot is so quick that in order to keep working with it, I started reversing the image or collaging in another pig.

Policed sow verso, 2022

The way you’re describing how you manipulate your source material feels very contemporary to me, almost computational.

I could just make those manipulations on my phone quickly and easily, which does feel contemporary. But college is an age-old process. Over the course of the past few years—perhaps because of the pandemic’s restrictions on seeing art in person—films have been a huge influence on what I’m trying to achieve visually with paint. I find films like [Morvern Callar by Lynne Ramsay and Zero Fucks Given by Emmanuel Marre and Julie Lecoustre] very exciting because they speak to how our contemporary ways of seeing have been cultivated and mediated both by technology and by the pressurized political moment.

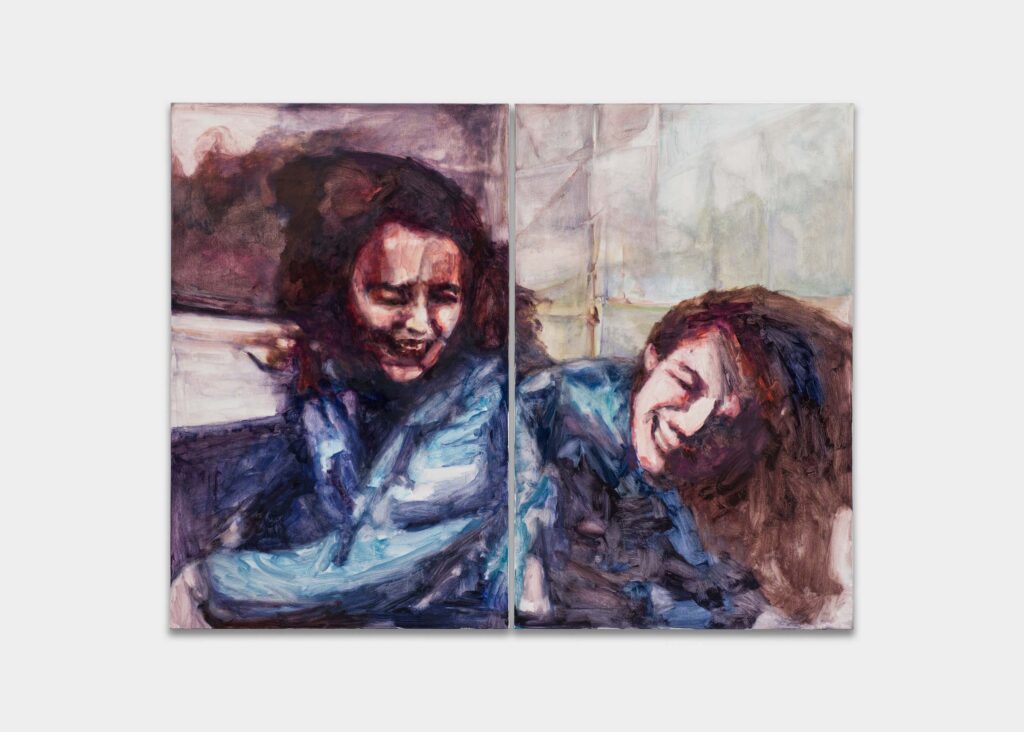

Do two halves make a heart? (JK), 2022

You tap into that in two ways: one, in your condensation of diverse references that form a whole within your body of work; and two, in the translucence of some of your marks, which resemble the motion blur of a degraded or low-resolution image. We are inundated with such poor images every day, and you’re representing them in a different medium.

Those images and ideas are behind my eyes as I’m painting.

I think quite a lot about the “surface tension” of my paintings—about how no single thing jumps out at the viewer more than any other. The word “kaleidoscopic” has felt important to me, both in my own work and in terms of other artists’ work, from Jutta Koether and her installation methods to films like Uncut Gems by the Safdie Brothers. In the latter, there is a really clever tension between the light and color that corresponds to the artificiality of screens. The way we’ll look at something on Instagram, say, is sometimes not that different than stepping out your front door and going to the shop. How you receive imagery on your eye feels electronic in that way. In my work, I try to use a surface which is stretchy, with marks that knit together, and where edges have enough fuzziness that, say, the edge of pig’s leg doesn’t necessarily supersede the dark background beyond it.

Smaller mouth, 2023

The stretchy surface you describe also imparts a sense that you are trying to capture stillness amidst chaos and motion, which makes the figures have an aching quality to me. Can you describe how the formal qualities of Uncut Gems have shaped your painting?

I don’t know if this is necessarily the thing that speaks most to the formalism in my work, but the opening sequence—which moves through mines in Ethiopia, a colonoscopy, gemstones, back through to a colonoscopy and into a hospital ward—was conceptually overwhelming and completely incredible. Beyond that, I am drawn to the film’s balancing of light and color, and how the cinematography makes you feel like you’re looking onto another vista at the same time as you might be looking at someone walking down the street.

The film puts viewers in an unyielding state of anxiety, both through its narrative pacing and its score. Somewhat similarly, in your paintings, a sense of danger, menace, or atrocity is always just on the edge of the painting—it’s being suggested, but not fully represented.

Living in the world in the last handful of years has felt rattling, like an increasing crescendo. That has just felt like a symptom of our time. Over here, there was Brexit, and there’s since been the pandemic, and the economic situation is shattering people. So yeah, the sociopolitical world does feel extremely worried and worrying, and I think that I am trying to touch on something about this atmosphere, that reality. I also am not interested in making pretty paintings. I wouldn’t really see the point in trying to make soft or easy images; I don’t think that would feel like it has much overlap with what we’re living. If you want to see pretty stuff, you can still go out to nature, or look at the ocean, or something.

Possession, 2023