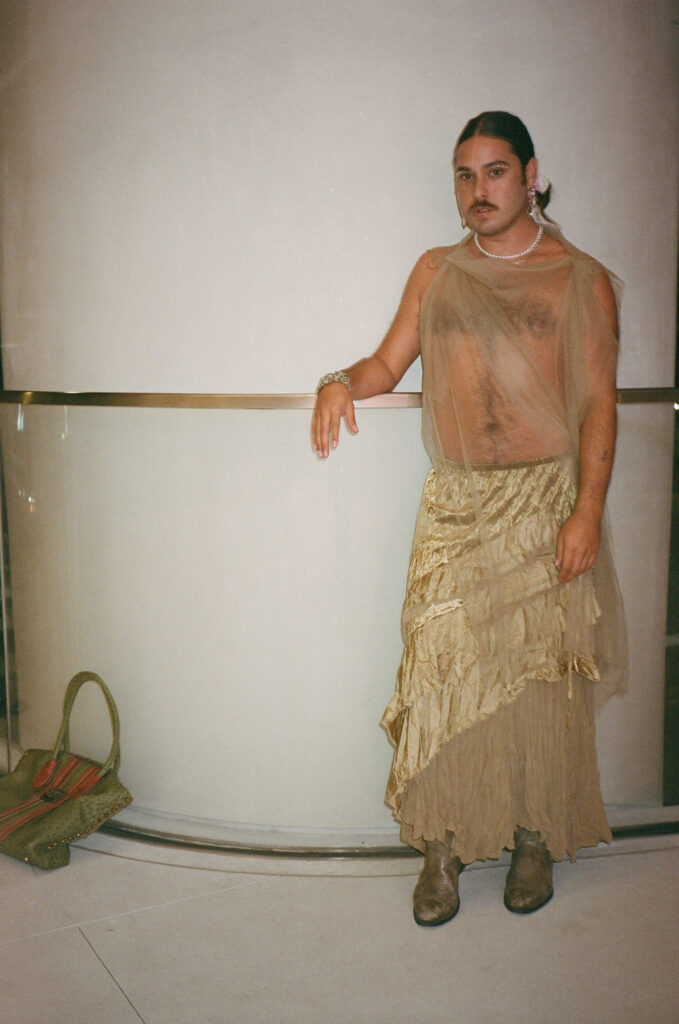

Marcel Alcalá

Interview by Shelley Holcomb

I was first introduced to Marcel Alcalá almost a decade ago when they were doing improv poetry in a McDonald’s Playplace on Sunset Blvd. A few years later, I interviewed Marcel for Curate LA about their first solo exhibition on their home turf of Los Angeles, and from there, we struck up a friendship. In the span of just a few years, I’ve been a witness to the evolution of Marcel’s artistic practice, developing from guerilla performances to small drawings of friends, to larger oil pastel landscapes, to full-blown oil paintings that now grace the walls of one of Los Angeles’s most talked about museum exhibitions.

As I was thinking about what words to write for this introduction, I was reminded of a quote by bell hooks when sharing about her own identity of being queer:

“Queer as not being about who you’re having sex with – that can be a dimension of it – but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

Marcel Alcalá’s art is a manifestation of this idea of queerdom. The recent success of their work in a museum setting surrounded by their peers is a testament to their ability to navigate and transcend the boundaries imposed by society or otherwise. To know Marcel is to know someone who isn’t afraid to not only stand in their own authenticity but also who is not afraid to continue the search within themselves for their truest self and who is brave enough to have an audience while doing it. The following conversation took place immediately off the heels of a magnificent night at the Hammer Museum—a celebration that marked the high point (thus far) of Marcel’s dream to be recognized for the artist she truly is.

MA: Hi, my name is Marcel Alcala. I’m an artist based in Los Angeles, California. I was born and raised in Santa Ana, California and my parents are from Jalisco. Mexico. Hi, Shelley!

SH: Hi! We’re speaking fresh off a weekend of celebration of Made in L.A. Can you talk about how you’re feeling right now? Post come-down and what your emotions were like before and during the show. I know you were very excited to show your parents your work that was hanging in the museum and what that meant to you.

MA: It’s always been a dream to be in the Made in L.A. show ever since I moved to LA. I feel like every time, the Hammer Museum Biennial showcases so many amazing artists and the city needs a biennial like this because there are so many artists in Los Angeles and because the city is so big and spread out, it can be hard to see all of the work that’s happening here. As someone who grew up in Santa Ana, it’s just such an honor to be in an exhibition like this. I think Pablo and Diana did an amazing job curating the artists–a lot of which are friends of mine or I’ve come up with in the queer and Latinx art worlds. I think this exhibition highlighted Chicanx and Latinx artists for the first time in a while. At Made in L.A, I think the positioning of my work is very interesting. I loved the article Ashton wrote about queer performers in LA who also make objects as a means of survival, but as performative people. That’s just a part of queer culture in Los Angeles.

Seeing my parents in that space was wild because I think they were the most worried about me as a child, considering I wanted to be an artist. I can’t say they weren’t supportive because they definitely were supportive of whatever I wanted to do. Being the youngest of four, I feel like they were just like, “let the bitch do whatever they want,” but they didn’t think that it was a viable option to be an artist, especially coming from a performance background. This was a super emotional moment for me because my parents could see that someone like me could thrive in a museum context. This is my first museum show. Although I’ve performed in museums in the past, I consider this way different because my work is being shown for three months and I also get to perform and do a panel discussion. My parents were shook that there was Banda playng at the opening, which basically started in Jalisco where both of my parents are from. I know that there was a moment where my brother, my mom and my dad looked at each other and we were like, “I guess the Latinos are in now because we’re all up in here.”

I feel like nothing was real until I saw the cover of the booklet with my work on it. Then I was like, “oh shit, this is very real. I’m just so proud of myself and thankful to the curators and the museum for supporting my work.

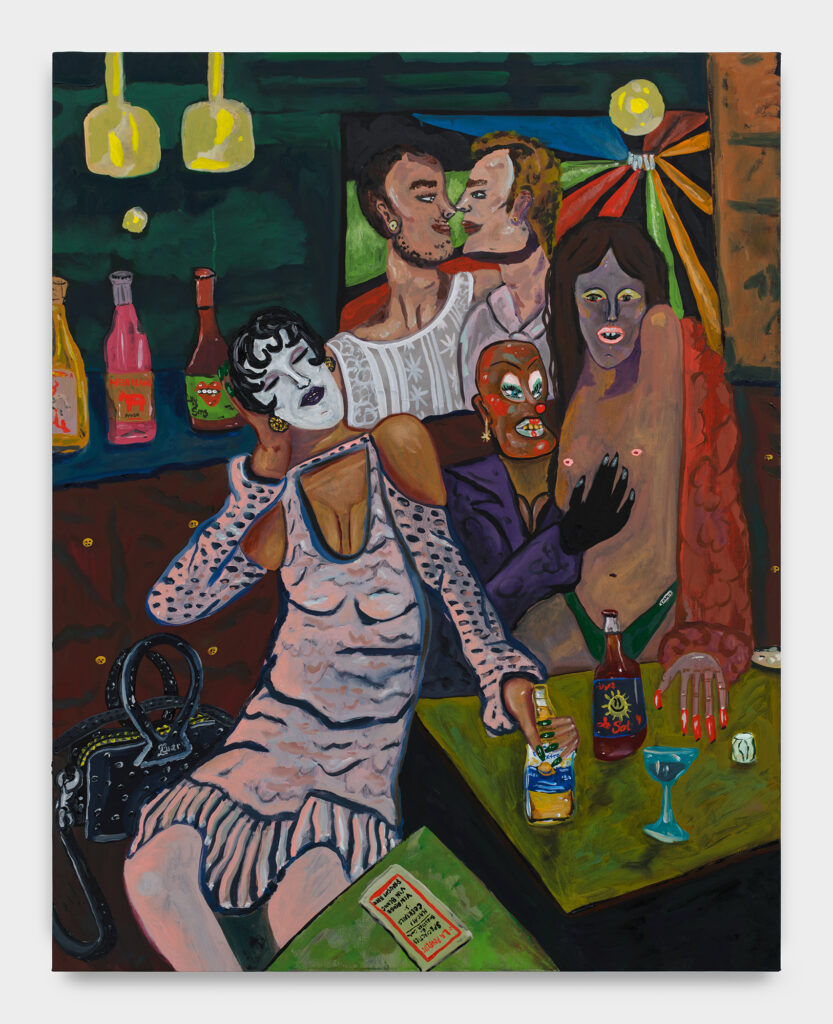

Marcel Alcalá, Midnight at La Poubelle, 2023

SH: That was my next question. You posted that your mom said Mexicans are “trending” now, and I’m guessing that’s because of the music that was curated by La Pau Gallery. Can you describe how it feels for you to see them watch these cultures merge?

MA: My parents don’t know what’s happening in the art world. So they were just shocked to just see so much representation of their life in a contemporary museum setting. Like my parents were born in the 40s. You know what I mean? So I feel like they’re a couple generations removed from what’s happening right now. And I kind of feel like my life is similar because of that. there’s so many different generations of Latinx style in California and in Mexico, Chicano versus like actual Mexicans from Mexico and. I mean. I think like, trendy to be like, wow. you never would think Banda would be playing at a museum. So they were shocked because they were playing old school tracks that hit. And that’s why my mom was like, “We got to go dance.” And I find it interesting, like I used to dance a lot to Banda as a kid, but of course, growing up in Orange County and then going to Chicago for art and just traveling abroad, I kind of lost those dance moves. And she was making fun of me. She was like, “Bitch, you don’t even know how to dance this anymore.” And I was like, Oh my God. I found it like almost one of those moments where it’s a remembering of this really inherent part of my life as a child.

SH: Right. And as a Mexican American and also queer Mexican American, you’ve been forced, I think, to assimilate in your lifetime. Right?

MA: Because they were born in the 40s, they also wanted us to assimilate because they moved here from Mexico. So they were trying to flee this thing and now it’s being celebrated by people that kind of have a nostalgia for it. It’s super interesting how it’s become almost like a form of hipsterness, but like, within the Chicano community, right? Which isn’t shade. It’s just like people who are into oldies.

SH: Okay, so after we left the dinner that night we went to a party at La Poubelle and you mentioned that one of the paintings that’s in Made in LA is called “Night at La Poubelle”?

MA: “Midnight at La Poubelle.”

SH: Can you speak about that? Who we see in the painting, what’s going on in the painting? And this is me trying to create a segue-way into you featuring your friends and community icons in your work.

MA: Yeah. I mean that night was interesting because it was a very like sceney party where there were a lot of actors, a lot of musicians, a lot of comedy writers and DJs. That night was six months ago and I put two of my friends in the painting who got married a couple years ago.

I work a lot with clowns in my work, so I wanted to add a clown and a girl who’s just a non-binary queen wearing this swimsuit, which is just a very typical gay swimsuit. It’s almost cringey, but I love that. The 1920’s girly has a Luar bag and I love nods to early 1900s oil painting. Especially lifestyle painters like Toulouse-Lautrec and also the spirituality-ness of an oil painting. I thought of the parties and the charade of it all where it’s a mix of non-humans and humans which I think of spirits and people I know or the spirits within the people that I know. La Poubelle is such a fun little dark cafe that reminds me of the French 1900s.

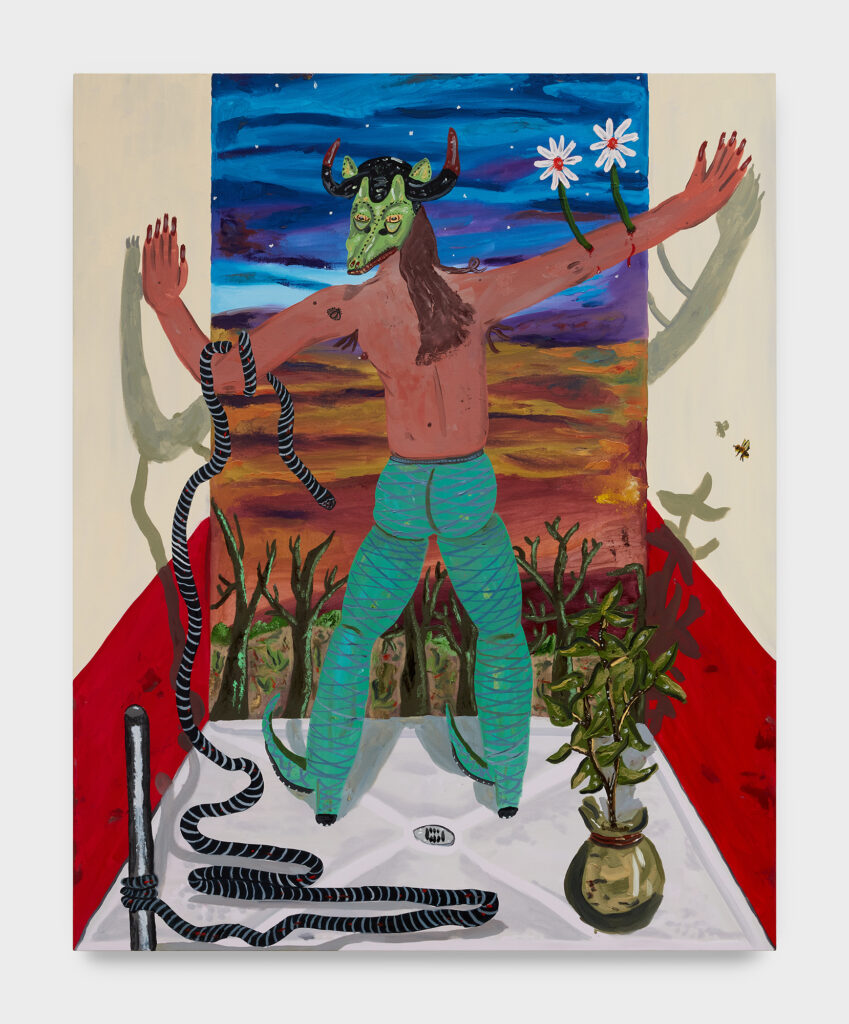

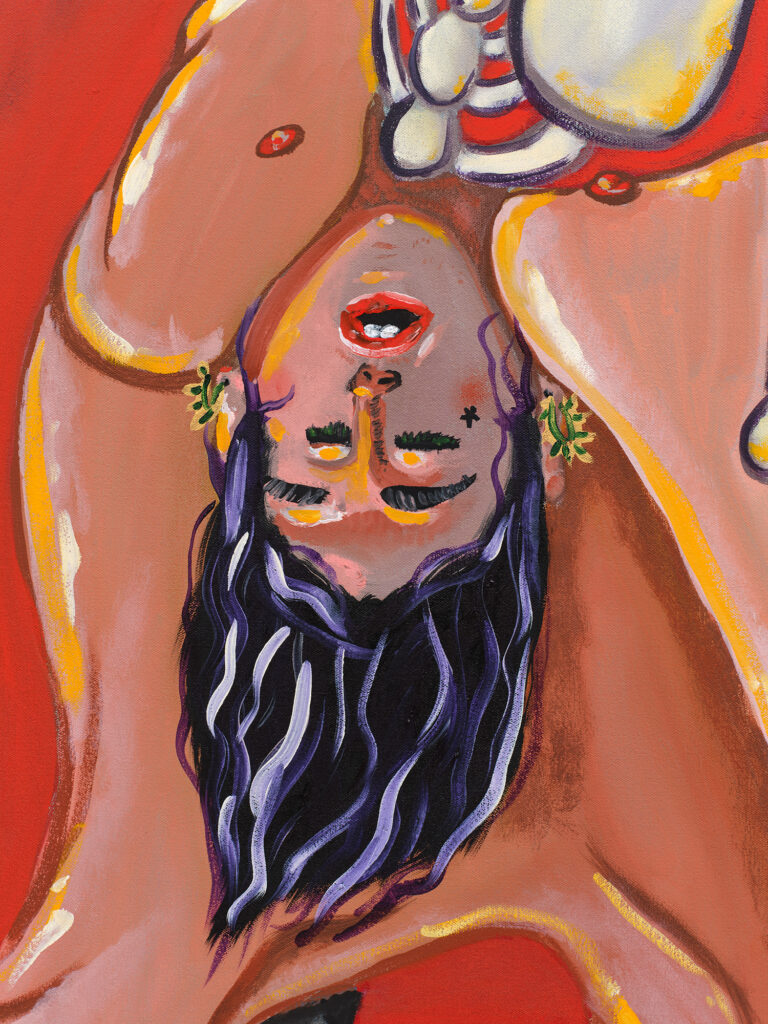

Marcel Alcalá, What’s on the other side must be better than this, 2022

SH: I had this question a little down the way, but I’m going to bring it up now because I feel like it fits with this conversation of your paintings, especially the ones that are in Made In L.A. They are, like you were saying, kind of this nod to traditional-ish style paintings of figurative works and still lives. Whether or not you do that purposely, I feel like that’s your groove right now. There was a moment the night of the opening where you were like, “should I start doing abstract painting?” And you had like a little mini freakout about figurative painting being dead, which is a conversation that I feel is always being had, people are always saying, “oh, figurative painting is so done with”, but I don’t think it ever will be. I’m curious how you feel about that and if you want to take a moment to defend figurative painting.

MA: I think more than anything, I’m just a comedy queen. If I want to make an abstract painting, I could just go ahead and do it because there’s so many types of work that exists. At the end of the day, if I do a minimal sculpture or an abstract painting, the history is already there. With my past work, I’ve done sculptures of girlies, which are very pop culture, smiley, with sad faces using gouache and oil. I’ve also done performance. I like the idea of the categorization of types of art, but I firmly believe in using all of the mediums to your advantage. Some artists will be like, “I make abstract paintings, period.” But to be an artist now and know about all of these different styles, it’s like I want to make an abstract painting and then I want to make a figure painting, and then I want to rub my butt on the wall and leave like the essence of my butt on the wall. I don’t want to limit myself into a box when it comes to work. I’m also interested in losing the identity-ness in the work now. But also, I know that if I make an abstract painting, it means like a queer Mexican American made an abstract painting, right?

SH: Yeah. It’s like what Erica [Mahoney] said, because she makes abstract work. She was like, “there’s still that identity in the work even though it’s abstract, it is still a huge component of making abstract art.”

MA: Yeah. And, you know, I poke fun and criticize the idea of a farm-to-table person making abstract paintings without having to talk about their identity. It becomes about form and people get super excited. If I make an abstract painting, no matter what it’s going to be, identity is going to be in the mix, and that’s okay.

SH: White people have the privilege of not having to speak about their identity in their work.

MA: I’m like, I still want to hear about your upbringing. I’m curious. I think we should all be held to the same standards. Just to not talk about identity is its own privilege in itself.

SH: So on that note, one of your earlier motifs in your work is the use of the smiley and sad face. What interests you in the juxtaposition of humor and tragedy?

MA: I feel like I’m finally starting to realize that my obsession with the smiles, and the clown, and in the juxtaposition of comedy and tragedy does come from an obsession with theater, and the idea that to be an artist is a kind of theatrical role that I like. To perform as an artist is its own thing. I like the otherness of being an artist and being able to talk about certain things, to point my finger at certain situations, but also to be a part of it. We joke about abstract painting and whiteness, but I’m also totally down for them. I’m into the fashion and storytelling of it all, the vibrant colors and the stories that come out of the experience of being an artist and making work.

SH: Right. And would you say that your paintings are a performance of your life?

MA: I think they are ephemera of being. That’s how I feel about all object- making and performance-making at the end of the day. A really nice looking painting is cool, but I’ve always been interested in the artist who made it.

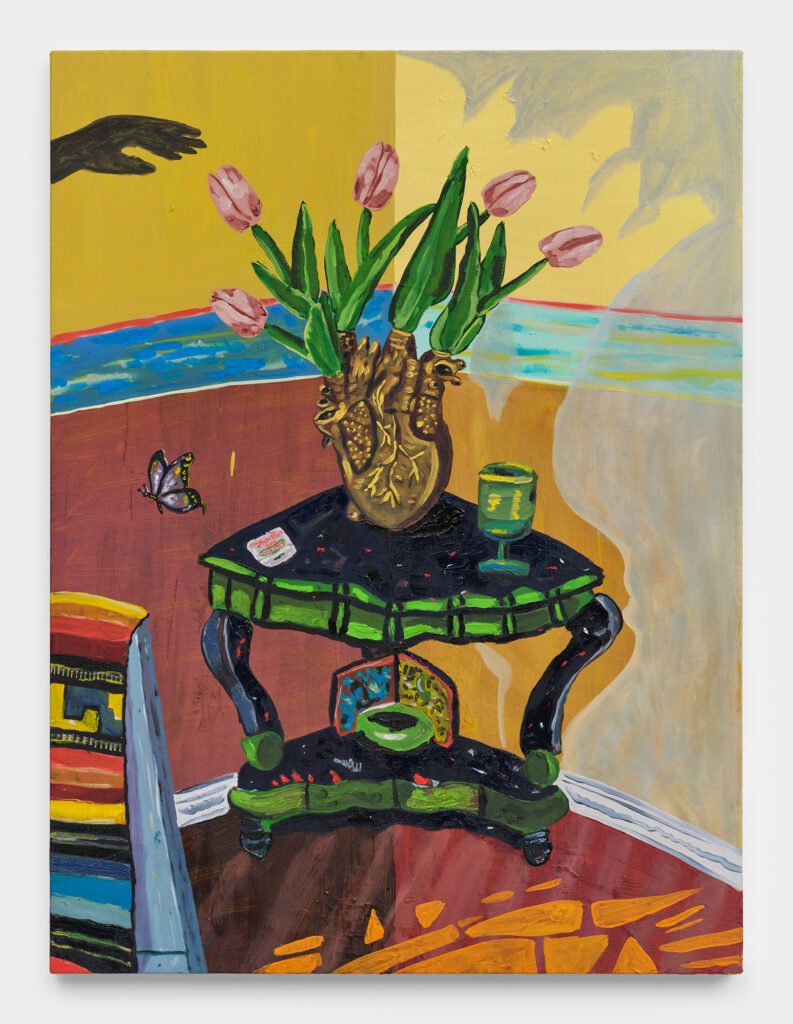

Marcel Alcalá, Heart Murmur, 2023

SH: Right. And your last solo show at Night Gallery was called The Performance of Being. Where did that come from? Because I remember when you had a ding moment for that title.

MA: I feel like that show was a really new step in a certain direction for my painting. I wanted it to have a super existential title that basically was a synopsis of what’s to come in the work. I find existing super fun and dramatic. I don’t even feel like I’m at the point where I want to be, but that show was a major turning point for me. And then I think Made in L.A. is also that. This year has been so poppin..

I’ve been into a lot of poetry again, so I want the mediums to consistently change. I do want to be a better painter, but I also want to be a better writer and I want to be a better photographer.

SH: Right? I’d love to also talk about your poetry because I think one of my earliest, earliest memories of meeting you was when you were dressed as a clown reading your poetry at a McDonald’s playground. And so to hear you say that you’re bringing more poetry back in, I think that’s very exciting. And I’m curious, what does that mean to your practice right now?

MA: It’s a nod to past work. I always thought writing kind of influenced the way I made a painting. I’ve only been painting lately which means I’m kind of in seclusion and can’t be literal about the things that I’m thinking about, which is also exciting, but then with poetry and performance I can still have this really outgoing personality and just be upfront about the ideas that I’m having. I think it’s because I’m an Aries, but whatever comes to mind is going to be released.

There’s this piece I’ve been working on recently called “Real Estate”, which is about a real estate agent in this non-wordly non-world who’s selling land. I’m going to be performing the final piece at the Hammer Museum on October 14th. I’ve been practicing it at this poetry night called Casual Encountersz. I think it’s a success, so I can’t wait to share that.

Marcel Alcalá, The Encounter, 2023

SH: Is it super personal?

MA: It was about this real estate agent who was selling land and whose hanging out with a couple dead bodies and talking about, basically disregarding the fact of like who was a part of the land and that it’s just crushed bones and how we are inside as humans, we have this tree that’s growing within us, whether alive or dead, that’s searching for light. Because the only way to grow is to find the light. So it’s a mix of being dark, but it’s also positive. That’s the whole dichotomy that I’m interested in. I’m playing this character that is also almost playing the narrator of humanity. Sometimes we’re not seeing what’s actually happening for selfish reasons. We’re this flawed character, but we’re also the hero. We might not look around us, but we’re still striving for the light through darkness, and some people are fucking dark. But I’m still down with humanity. Not completely down, like, fuck it all, but, like, I’m into it.

SH: So this is kind of my last question and I think this is very much in this vein of where you are at this point in your life. There was this painting at the Hammer that I didn’t get a chance to talk to you about, but I actually really wanted to, which was the biggest painting you had with the skeleton whose skin was coming off. And they’re staring into the mirror. Can you tell me the title? And explain to me what’s happening in this painting exactly?

MA: The piece is called “The Encounter,” and I wanted it to be in this kind of spiritual, dreamlike place where the skeleton can exist. I guess recently I’ve been obsessed with the idea of being born in the body that you’re in and you have no choice. We are all just skulls that are very much the same. I’m also obsessed with how even with the body that we live in, it’s still temporary, but it’s also super limiting to the experience of being or like, being alive. And I thought it would be interesting to make a piece where the skull is alive and just shedding off its skin. Looking into this other space where this other skeleton is thriving and wanting to join in with the skeleton to go join in and do whatever because it’s clearly having a good time. And sometimes, like the act of the body is that, it’s limiting. So it’s just trying to be like all the girls and just trying to maybe get away from this, like, desolate, spiritual place.

SH: So is it a self portrait?

MA: I don’t know if, I mean, I feel like everyone looks at every piece and is like it’s a self portrait. I guess because I made it all and I sometimes use a similar body skin to mine. I think I want to stop doing that because I don’t want to fear portraying other body types, and I think sometimes I do just because of such an inherent fear of cancel culture. I have a diverse friendship, diverse experiences, so soon I’m just going to be I’m going to paint like everybody.

I love the idea of shedding the skin and being free. Free of like the shackles of light refracting onto your body. And then that you are being projected onto shit, whether it be about your gender, like the color of your skin, how short you are, how tall you are, everything. Whatever. It’s gay.

Artist

Interview

Shelley Holcomb

Photography

Nik Massey

Contents Culture Editor

Juan Marco Torres

Web Layout

Naveed Shakoor