Interview with,

Khalik Allah

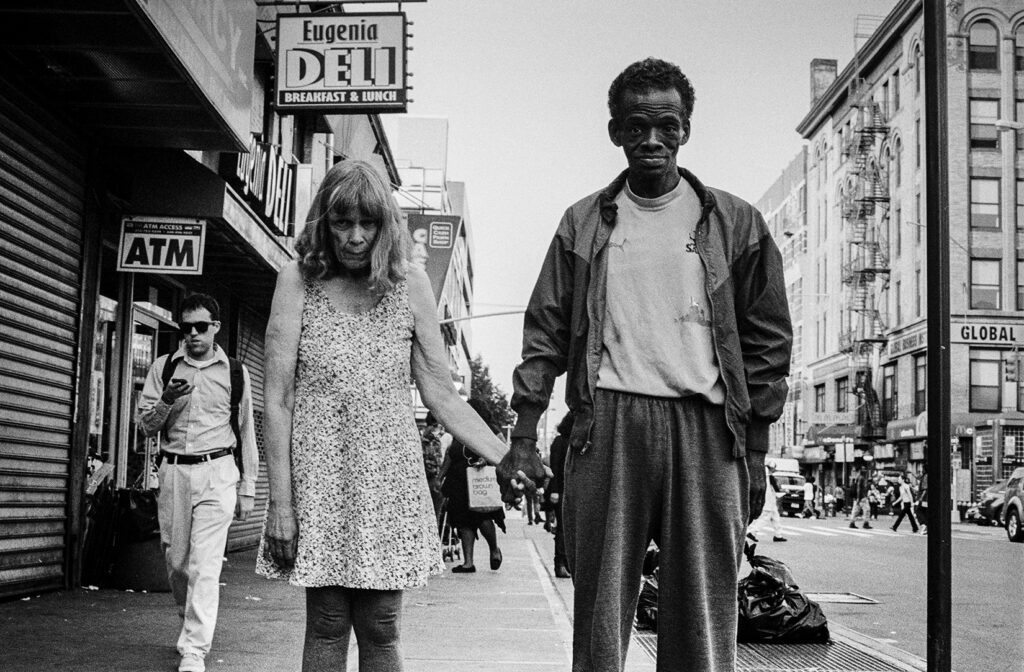

If it is the drama of the man that lies behind the eyes, then the street is the stage that houses the characters in Khalik Allah’s “street opera” that is his photography. Allah documents the lives of his subjects, most of whom are unhoused, capturing them in their natural environment of the streets of Harlem. These portraits serve not only as an allegory to who these people are but also as a mirror or reflection of who we are as a larger society. Allah’s photographs are a visual storytelling of the existence of so many who are many a time overlooked, and they give a voice to the people who are often voiceless.

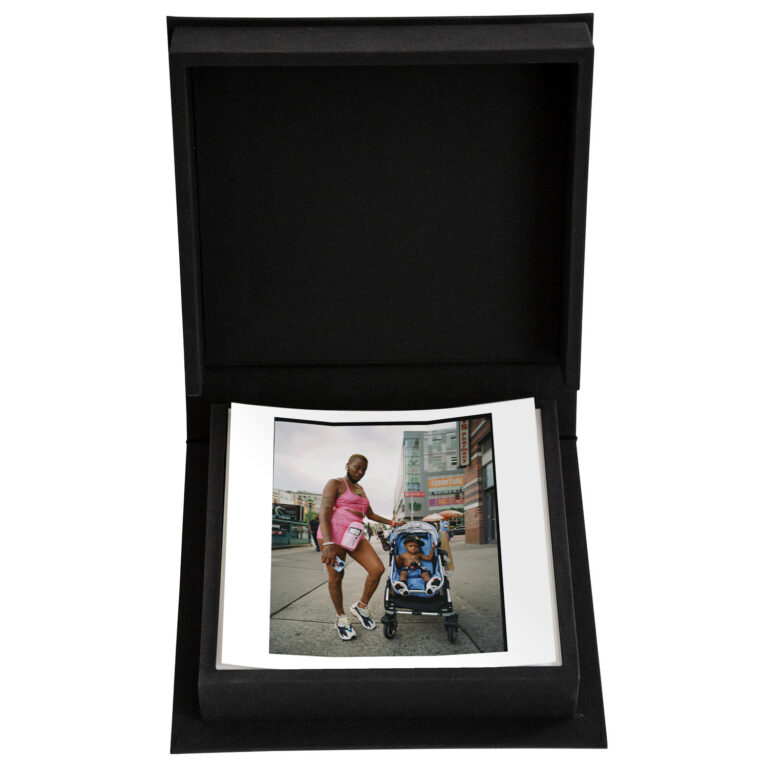

As part of Magnum Photos’s 75th-anniversary, Khalik Allah’s photograph Man Child was chosen among these 31 works to participate in the latest in a series of three Square Print Sales looking back over its illustrious history from 1947 to the present day. The October sale is curated in partnership with The Photographers’ Gallery in London, which has invited 31 photographers it works with to join in by contributing their own iconic images. I recently had the opportunity to speak with Allah about this work, in particular, its significance, and what it means for the artist to peer into the souls of the people we pass by everyday.

Shelley Holcomb: Your work has been described as “street opera,” and that it goes beyond street photography, can you elaborate on this?

Khalik Allah: Operas are very expressive of emotions through music, they’re rhythmic, and I feel like both my photography and my filmmaking are rhythmic and musical. A lot of my portraits have to do with expressionism and the depth of a person through their eyes. This is why I call it street opera because the streets are my studio. The whole world is a stage.

SH: What draws you to portraiture? And specifically, the portraits of the subjects you choose?

KA: It feels like I’m making historical documents of the lives of people who live in the streets. Also, what that says about us as a society? The portrait is not specifically only about the individual that I’m photographing, it’s a larger statement for the city and for the world in general. Portraits show both resilience and strength of the people I photograph, who, despite the effects of drug addiction, homelessness, or oppression, there’s still a light shining within them. They’re still beautiful. This is what really draws me to the people I photograph.

SH: What story do you see yourself telling over time?

KA: A story of resilience, a story of integrity, a story of respect. For other people and for myself, a spiritual story, a story of people’s spirits. Ultimately, that story isn’t finished, it’s still being told now. My work is evolving and expanding into other realms, but I’m speaking about my work specifically on 120/5 Street and Lexington and my larger body of work, which is now being shot in Jamaica

SH: There’s a quote in your artist statement that says, “photography and film-making form a Venn diagram in his work.” – what’s in the middle?

KA: I started off as a filmmaker, and then I got into still photography later on. I always looked at it as the same visual language and expression, whether it was with still images or moving images. But those are two different businesses in terms of how they are presented in the world. You got the film business, and you’ve got the photo industry.

To me, creatively speaking, they are still very similar. If I’ve been shooting photographs for an extended period of time, it’ll make me want to make a film because the still image can’t depict everything that the moving image can. Sometimes I’ll be hearing sounds or seeing certain things that are better suited for motion rather than still photography. So it goes the other way, if I’ve been making a film for an extended period of time, I may just want to stop for a while and get back into photography, you know, a sharpened still. Both practices sharpen each other. I exist where that Venn diagram overlaps, whereas I’m a photographer and a filmmaker, my films are informed by my photography approach, and in that, their photographer-style documentaries. My still images are informed by my filmmaking in that they are cinematic, My still work is supposed to look like a motion picture.

SH: I feel extremely drawn to the eyes in your portraits, and the subjects seem to often stare straight into the camera, is this intentional, and why?

KA: In portraiture, there’s an emphasis of focus on the person’s eyes in the nighttime. I feel like they cut straight through to the viewer, where they can pick up on the energy of the person I’m photographing, and even my own energy. The viewer is able to pick up on the energy of the interaction between the photographer and the subject, and it all comes through in the eyes. That level of intensity and that level of intimacy are depicted through the view of the subject. In my work, it’s not as if the power dynamic is offset. I, as the photographer, am not in any way more powerful than the person I’m photographing.

Being able to photograph at nighttime and move safely throughout the years really took a certain level of mutual respect between myself and the streets, between myself and the people that I document. I think that’s what comes across in the eyes of my subjects, as well as the reality in which they’re living. Ultimately, I’m not just photographing the streets and taking pictures of the buildings. I’m depicting the environment through the eyes of the person that I’m photographing.

SH: In one of your past videos, you can hear your interactions with your subjects, What goes on for you behind the scenes? Do you have a particular process?

KA: It’s not like there’s anything necessarily going on behind the scenes. The pictures themselves are the behind the scenes. The images themselves are something that somebody usually would not see, you know, or it’s the sort of person that they may usually avoid if they see them at nighttime. I think that’s what gives my work the strength it has–that is confrontational, not in an aggressive way, but confrontational in the definitive way that it’s confronting the fact that these people are easily discarded or turned away from, and it’s putting them front and center for the viewer to look at this person and their relationship to this person. It’s allowing the viewer to understand that you do have a relationship with this person, even if they seem separate.

SH: What is your story for the photo that was chosen for the Magnum Print? Is there a title?

KA: I call that picture Man Child because the child in this image really looks like he’s thinking like a full-grown man, even though he’s in a baby’s body. He got gold around his neck, a fresh pair of shoes, and a hat as if he dressed himself, and it just seems like, even at that young age, he has a level of maturity. I think that’s partially due to the reality that he’s faced with, his environment, and the circumstances that he will have to face growing up. When I see this child, I don’t just see an individual, I see the generations of men, women, and children that it took to create this child in an environment of so many struggles to face in order to even exist.

This picture was taken on 1/25 Street, in Malcolm X in Harlow. It was a spur-of-the-moment type of thing. Just as I saw them walking in, I asked to take a few photographs. It was July, a special time of the year to shoot because July in New York brings about a certain energy in the streets where people are free, and people are out enjoying themselves, but also, you got to stay on point, everything is still real. This image represents the summer of 2022 and the work that I was doing throughout that time.

SH: I was watching your films, and there’s a conversation at 17:26 of Antonyms of Beauty where you talk about the mathematics of photography and your application through life in an artistic form, you say, “Everything we see is light.” Can you talk a bit more about this and how it relates to your portraiture?

KA: Photography and filmmaking are just vehicles to express deeper spiritual ideals that I hold. In truth, everything is light. There’s no darkness or shadows anywhere. The mechanism that we use to see, the physical senses, specifically the vision, is not always accurate, you know. But when you see through your heart, all you’ll see is light. This is also a statement that I’m making, in terms of recognizing the light, the inner light in other people. When you focus on the light in others, it reinforces that within yourself. My application of mathematics really has to do with understanding that math is a universal language. The mechanism of a camera is a scientific instrument that deals with light in the form of an aperture. Everything we see is light.