Interview by Juan Marco Torres

Melanie Pullen is an artist most known for her photography series like Violent Times and High Fashion Crimes Scenes. Starting her career shooting iconic rock bands like The Black Keys, she eventually transitioned into a haunting exploration of crime and glamour. Pullen is not afraid to push boundaries, and her cinematic work provokes profound questions of the world around us. I had the pleasure to ask the photographer about her career, her creative vision, and her plans for the future.

Above: She Sees Everything

Q: I read you started photographing a lot of rock bands like The Black Keys. What made you transition into fine art photography?

A: I grew up with a family of artists and really had no formal training as a photographer, so my approach was always as an artist. I knew I wanted to do an art series and really find my own style as a kid but I lacked formal training and my family didn’t have the funds to send me to art school. So shooting bands was really how I taught myself to do the basics in photography and get paid to learn. It was something I also really loved too because I got to work with so many talented people. Music has always played a big part in my process so this was a great way to learn.

Q: Can you please tell me what intrigues you so much about crime-scene photography?

A: I find historic crime-scenes to be fascinating. They sort of tell a long lost story, of a person, a city, a style. I’ve found so many interesting ones from the turn of the century through to the 1950’s where the crime files were lost but the photos told a tale that led down a certain path. When I found a very interesting crime scene photo it would take me into this historic realm and I’d see the whole story unfold right there.

Q: What boundaries are you trying to push with your characteristic combination of commercial and journalistic photography in High Fashion Crime Scenes?

A: Mostly, I want people to be lost in the distractions. I’m purposely desensitizing the viewer. I intentionally make their eyes wander to the perfectly beautiful shoes and then as an afterthought notice the fact that there is a woman hanging from a noose. It’s the sort of thing the media does daily. We are a desensitized society, so I’m playing this up and taking one on a journey to see this in the end by glamorizing it (literally). This is what the media does but for different reasons. I’m more interested in this personal reflection through my work.

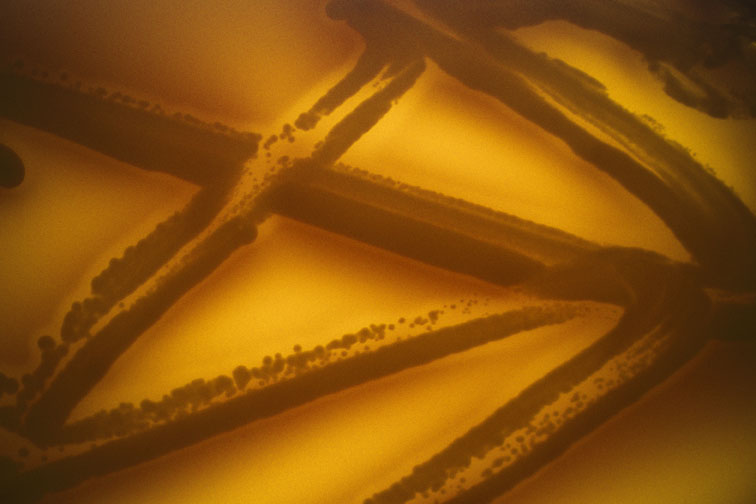

Above: Biowarfare Series

Q: What is the effect of the intermingling between fact and fiction in your work?

A: Mainly the “fiction” is the glamour, the fashion, the colors. I use the clothes and style to give a sort of identity. It’s something that is presumed in our own lives: if we walk down the street and see a man in a uniform, we know he’s an officer; or a woman in a fur coat and diamonds, we assume there’s some wealth. So the clothes can tell a bit of a story and give the victims in my images an identity. I do use fashion to also play with the viewers senses as well, directing their attention to where I want it to go. It’s subtle but it’s been a powerful tool for this purpose. There are many layers to the way I shoot photos really and the purpose behind the choices I make. Even the locations, I use very cinematic lighting to dress up the locations and create a more cinematic version of the original crime scene that I’m inspired by. All of these things are a path through my imagination in the end, how I see things, imagine them, and then of course they are my own personal style. It’s really a glimpse into my imagination.

Q: Where does your custom design inspiration come from?

A: Well, I love timelessness in photos and fashion. I like it when you can view an image and it seems as relevant today as it did when it was taken. So with High Fashion Crime Scenes, Violent Times, and other series I’ve shot it was really about not dating my work through fashion or film and creating this elegant timelessness. I think I mostly did that in High Fashion Crime Scenes, any of those images could be today, yet they’re almost 20 years ago now.

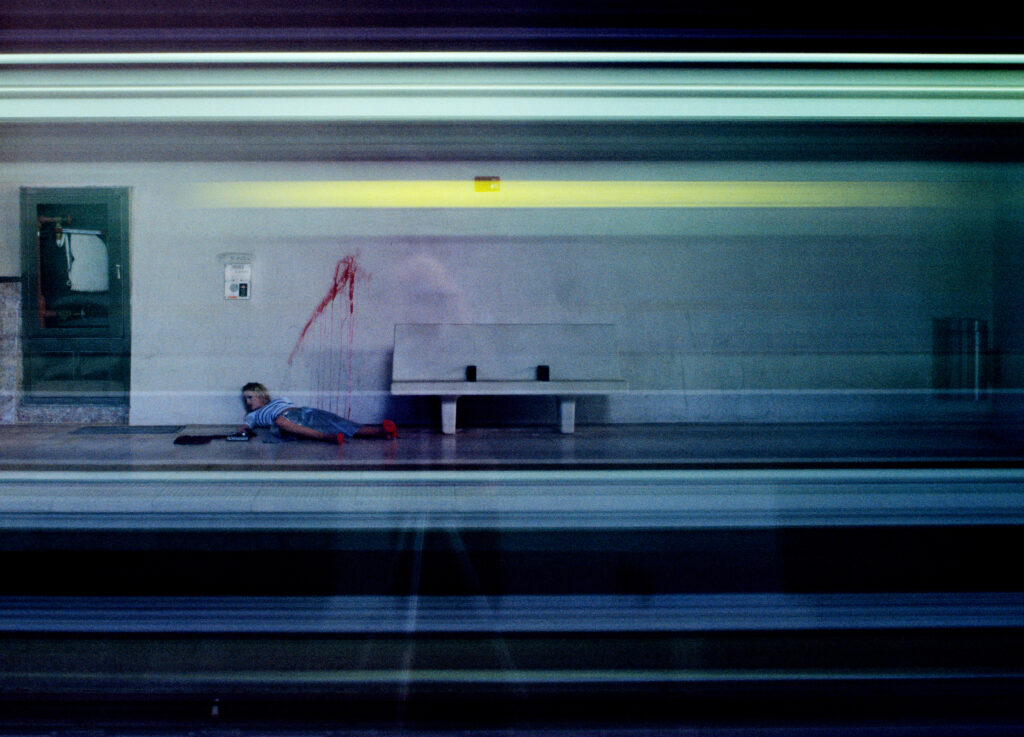

Above: Lauren

Above: From the Nina Hanging Series

Q: Your Crime Scene work has been shown around the world. Has the reaction to your work been different overseas than in the US?

A: The underlying feeling is interpreted the same in most places and the way people react. In Japan I have a big sort of cult following, a very interesting group follows my work there. In Korea, I had lines of people for days to see my work – just a very amplified version of a show here – with massive amounts of people. So it’s just slightly different all over but the same idea I think.

Q: How do you choose which crime scenes to recreate?

A: It’s usually a crime scene photo I find that mentally I get lost in, sparking questions like: Who is the victim? What is it about the room? The wallpaper? There’s always some sort of mystery to me in the ones that I choose, something haunting.

Q: Where do you think this innate need for glamorization comes from?

A: I think honestly in the media it’s just sensationalism. They have to add in music, a story, mystery to keep the viewer focused. Now they add sound effects, camera angles, etc. In all reality, a true crime scene is very quiet and final. Not much happening. I’ve worked with the Coroner’s Office and the forensic center here in Los Angeles so I know when you are at a true crime scene – it’s just very quiet and still.

Above: Loves to Kill Time

Q: You held a performance at the LA Art Show back in 2017, what propelled you to experiment with performance art?

A: They asked me to create something there and I really am a fan of film and dance. So I decided I would bring my work to life and allow the audience to interact and be able to walk up and be in one of my pieces while playing with people’s senses. I sort of wanted to break some rules and play with blood, music, sounds. It really became about me having fun with what I do and a motion forward.

Q: In the segment from your series Violent Times titled The Biochemical Warfare Series (2008) you depict a microscopic view of the infectious disease Anthrax. Looking back, how does your exploration of the future of war reflect the current situation of our world today?

A: I always knew the future threat that could tear up our society would be microscopic. It was this instinct of what could drive us into chaos and now with COVID-19 we get a sense of what that is like – just imagine it with something super deadly as a biochemical weapon. This is pretty close to that and a sort of wakeup call. We see the holes in our medical system, governments, and that it doesn’t take much to overload our world. It’s kind of scary, and as a society (as humans all together) we need to be better prepared in the future.

COVID-19 is a test run and I just hope we don’t lose sight of that and how important it is to be much better prepared once we’re on the other side of this.

Above: Last Light

Above: When You Feel Something

Q: Do you also have an idea beforehand of how the audience will react to your work? Is there a particular reaction you’re aiming for?

A: I really don’t think about that as I’m creating the work. It’s extremely personal when I’m creating the work, it’s really about something deep and internal. When I show the work to an audience there’s always this moment right before the first show where I go, “okay, here we go”, and I have to take a breath and let go because it’s a piece of me… I guess in music you would say when someone is deep into their process it’s “soul”. It’s the same with art when you really dive in – it’s one’s soul. So I’m sharing my soul a bit and the audience will have all sorts of reactions really that sometimes has nothing to do with me or what I’ve made. I find their stories interesting as well in the end. For art to actually work, it has to have some sort of impact on the viewer or else it’s essentially meaningless. So I’m glad some people find my work has meaning or impacts them somehow. Even when it’s received by someone in an adverse way it’s still affecting them somehow. I think if I did a show and this didn’t occur in any way whatsoever, I would know that maybe I wasn’t invested enough in my journey.

Above: Phones

Q: Most of your series have taken over a decade to create. What is your favorite part of your creative process?

There are a few moments in the process I enjoy the most: the gathering of the story, when I’m piecing it all together, and then when it actually comes together! After I’ve shot the work and I start editing, it becomes some sort of puzzle and I love that – when the pieces start to all fit together. It’s all so personal to me. I edit all my own work, so that time alone with the images, after large shoots and long planning – that’s really magical to me. I get to internalize it and really perfect it with the final retouching.

Q: I read in your interview with SuzAnne Steben that you plan your shows before even having produced the actual art for them. What kind of projects are you envisioning for the near future?

A: I’ve been working on different book projects and I have a series that I’ve been working on for years that is a culmination of everything I’ve done to date.

I’m also playing a little with motion pictures and have some ideas – but sadly most things are now on hold during COVID-19. So for now, I’m really working hard on my photo books since my shoots generally involve lots of people. As soon as it’s safe to have large groups together again, I will be back shooting and I cannot wait.

Above: The Watcher

Interview by Juan Marco Torres

Editor | Deborah Ferguson

Artwork | Melanie Pullen

Web Layout | Allie King