Mauro C. Martinez at UNIT London

Interview by: Luc Sokolsky

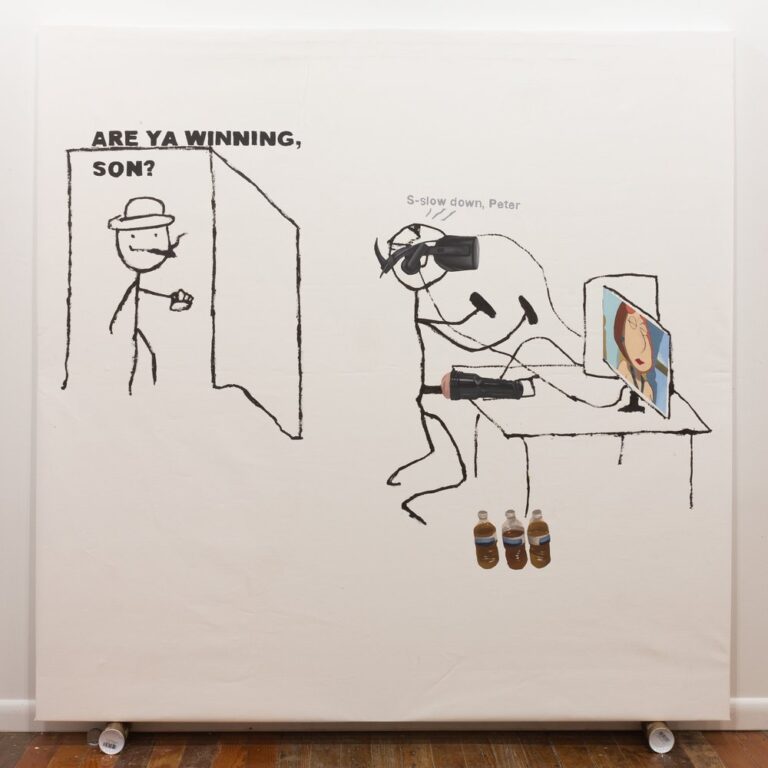

Known for his reflections on digital culture, the Texas-based painter Mauro Martinez’s representative paintings often depict memes, censorship warnings, and other familiar digital icons, seen from a new perspective highlighted by the enlarged scale and attentive mark making. Martinez and I spoke about his latest work, which focuses on the people and connections that breathes life to this digital consciousness. Through a series of new paintings and a new foray into sculptural work, Martinez offers a sympathetic look into the lifestyle and home of gamers, who at many moments seek community in digital realms. Examining the preponderance of technology in daily life, this lifestyle is seen through the framework of Nietzche’s philosophy, questioning the morality of contemporary lifestyles.

Luc Sokolsky: The title of your exhibition, The Last Man, references Frederick Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, a philosophical tale of an enlightened man sharing his wisdom on human purpose, and the futility of religion. What is your take on Nietzsche and his supposed nihilism, and how does it relate to your latest work and contemporary society?

Mauro Martinez: I anchored my current body of work to this parable in response to meme trends and discourse on TikTok, which has become an increasingly vital resource for me. I noticed a trend on the app addressing Nietzsche’s parable of The Last Man in reference to nihilism specifically and the general take was that it’s a prophetic reflection of today’s tech-obsessed society. My body of work aims to look at this reliant condition through a more sympathetic lens — not as a moral failure of the individual but as a direct response to trusted institutions that started to fail them. I think it is difficult to blame an individual for feeling nihilistic when they have no job security, no affordable health care, an education system that drowns you in debt, stock markets that are gamed and an art world with narrow gates for entry. Our ability to create communities and flatten hierarchies via the internet may be a product of innovation, but it was born of necessity and oftentimes desperation. If the work reveals anything about our society it’s simply the very real and persistent desire for meaningful human connection above all else.

LS: Recently, research has supported the idea that many people seek and find community in online spaces, and find more support doing so than in “real life.” How have your experiences in online communities affected your perspective regarding connection via the internet?

MM: Having been born and raised in a smaller city, I took advantage of online spaces as soon as I could. While I can point to things like harassment campaigns and cancellation efforts (both of which I have been at the receiving end of) as being very real pitfalls to these spaces, most of my experiences have been overwhelmingly positive. My experience with my own close group of friends is a great example. They’re big gamers and around the time of the pandemic lockdowns I started joining their daily voice chats to keep in touch where I otherwise depended on in-person hangouts. I normally paint while they game and every now and then I’m still caught off guard when someone suddenly yells, “Bro I have lacerations on my hands, get me to the hospital!” I continued participating in the daily voice chat ritual with them and we now spend an alarmingly considerable portion of our days together in virtual parties.

LS: There is a dichotomy between isolation and connectedness in the online gamer. How does the solitude of their physical reality balance with the communities bolstered by online participation?

MM: This specific condition could be a body of work itself because it’s so unique to our time and really forces us to reconsider our definitions of solitude and community. Ultimately I think the crux of this dichotomy lies within the inherently sedentary nature of being online and the mechanisms in place to bring/keep us there. It’s a format that defies general conventions for better or worse.

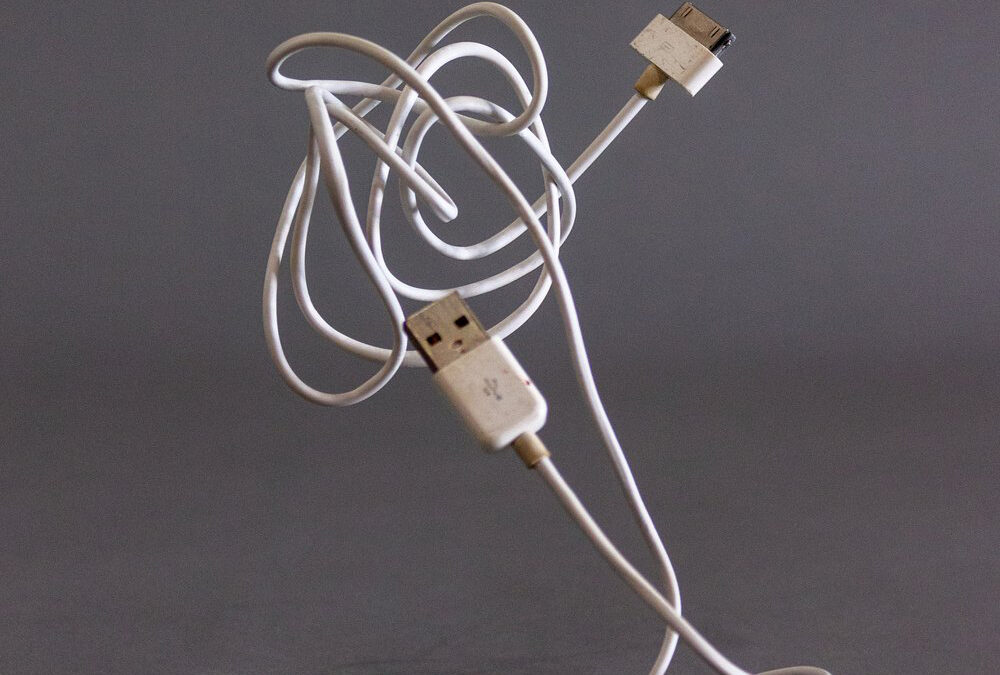

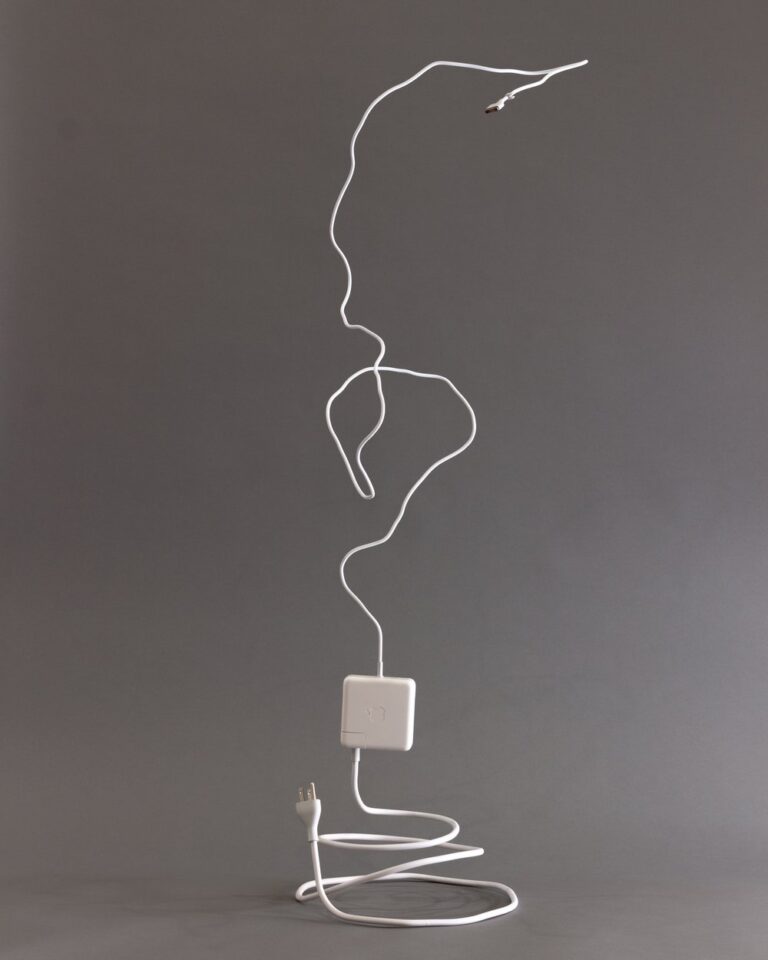

LS: In the piece Zarathustra, a MacBook charger is personified by form and title. Uncoiling the charger and standing it up denotes our reliance on power for connectivity, thus elevating the importance of the charger itself. What commentary does this series of sculptures make on our technological reliance?

MM: Like the prophet in the book, the sculptural Zarathustra issues a similar warning of a life lived for consumption over creation, a nihilistic condition Nietzsche calls “The Last Man”, the antithesis to his “overman”. The sculpture itself is positioned in front of the largest and busiest painting in the show: a cluttered gaming setup also titled “The Last Man”. The sculpture first draws the viewer’s interest only to lose it to the chaos of the painted scene. Together these two works are meant to walk the viewer experientially through Nietzsche’s parable, where the prophet is ignored while the crowd embraces the condition of the last man. I think the viewer’s transition from the MacBook sculpture to the oil painting in this context underscores a sort of false equivalency between morality and our level of involvement with technology.

LS: The sculptures in The Last Man represent a new forway into three-dimensional work for you. How does the implementation of your ideas and process differ in creating sculptural works, if at all so?

MM: For this body of work, the paintings very much directly informed the sculptures. When I was painting The Last Man, the wires were left to the end simply because of how tedious they are to paint. Seeing them on the canvas as blank white strings across the canvas made me reconsider their importance. The way they seemed to be floating as unpainted segments on the canvas directly gave me the idea to have these objects physically rising off the ground. They were very much inspired by the paintings.

LS: In War Crime, the subject holds a PlayStation controller, covered in grease and cheese from a pepperoni pizza. As many online video games are based in violent scenarios, are you worried about the transfer of violent tendencies?

MM: Personally, no.

LS: What is your personal philosophy as it relates to nihilism and Nietzsche’s work?

MM: As a recovered heroin addict I definitely think there’s something to be said about personal responsibility. There is so much that is within our control and within our reach. But I also remember that two semesters into my art school education the banks decided to stop approving my loans and I had to drop out. For as much as I have come to love my own journey and path I sometimes wonder if some of the suffering along the way could have been mitigated if pursuing an education simply hadn’t been so expensive.