Photo: Julian Burgueño

KRISTIN REGER

Interview by Juan Marco Torres

Kristin Reger is an American multidisciplinary artist. Born in Chicago and currently based in Mexico City, she recently debuted her latest series titled IUDUIUDUI with art gallery Relaciones Públicas during the Zona Maco Art Week – a post-humanist exploration of performance, sculpture, and fetishism as a port of entry into the unknown. The exhibition was held at Edificio Ermita, an architectural landmark in the city and where I had the pleasure of sitting down in conversation with Reger about her visionary work for ContentsCulture.

Photo: Fabián Valdes, courtesy of Relaciones Publicas Art

JMT: Congrats on your show! Can you share with me a bit about your journey as an artist and how you started.

KR: I’m from Chicago, my family is from Germany. My dad was American though, he and my mom did light shows and posters for bands like Jefferson Airplane & the Grateful Dead (haha). They were always into music and psychedelia. Amon Düül, prog rock, that kind of stuff, but also JRR Tolkien and other fantasy writers. Everything was shapeshifting and fantastic, that was “normal” and definitely had an impact on me.

I’ve always been interested in fashion, in part because it was a cultural thing to embroider from a young age in my family. I read a lot of theory in college about clothes and later worked in the industry, but the commercial side wasn’t ever that compelling. That’s what led me to art. My first projects came from drag in New York. I was sewing all the time – creating a reality.

I moved to Mexico in 2013 to get an MFA. It was more about displacing myself – going deep into an unknown. I came here on my own.

JMT: Since we are talking about Mexico City, what is it about this place that is so special to you and allowed you to expand creatively?

KR: I’m still surprised by Mexico City every day– that is something I need. Seeing and experiencing iterations of human expression creates psychological possibilities for me. The people here are just living, doing their thing. Not necessarily thinking about this layer of history or that.

Meeting Anto (Antonella Rava, the director of Relaciones Públicas, our gallery) in 2018 gave me more of a place here. That sense of community allowed me to put all of my juice into the studio.

Photo: Fabián Valdes, courtesy of Relaciones Publicas Art

JMT: Fetishism seems to be a central theme of your pieces. What motivated you to explore this concept?

KR: I read this book called Feminizing the Fetish, that was the original title in the first edition, by Emily Apter. It talks about fetishism in fin-de-siècle French literature. It was really a genre of its own, and there were two particular chapters that really blew my mind, and gave me the basic concepts for how fetishism works the intellect.

Fetishism, in my mind, works in two ways. First of all, there is a fundamental replacement, a compartmentalization of the body that happens through fetishism. The body is split up. I think about this all the time and it comes very directly from having thought and read about fashion. In the West, the body is thought of as parts that can be made, replaced, altered, and this is not only in costume. It happens in Western medicine as well. Western medicine approaches the body in a very area-specific way, as opposed to a more holistic approach we might see in the Chinese tradition, or Ayurveda, for example.

Second, there is all the cutting-up and replacement or “chiasmus” happening that becomes a safety thing, particularly in sex. The body is conceptualized or physically partitioned and reconstituted in a way that it is a little more familiar. I think it’s similar to how a child learns to conceptualize the eye as a circle or almond.

I remember being in Berlin and cracking up reading people’s Tinder bios talking about “I don’t want any vanilla people who are not into this or that”, and it’s just like, well, you are the vanilla one actually, haha.

Photo: Fabián Valdes, courtesy of Relaciones Publicas Art

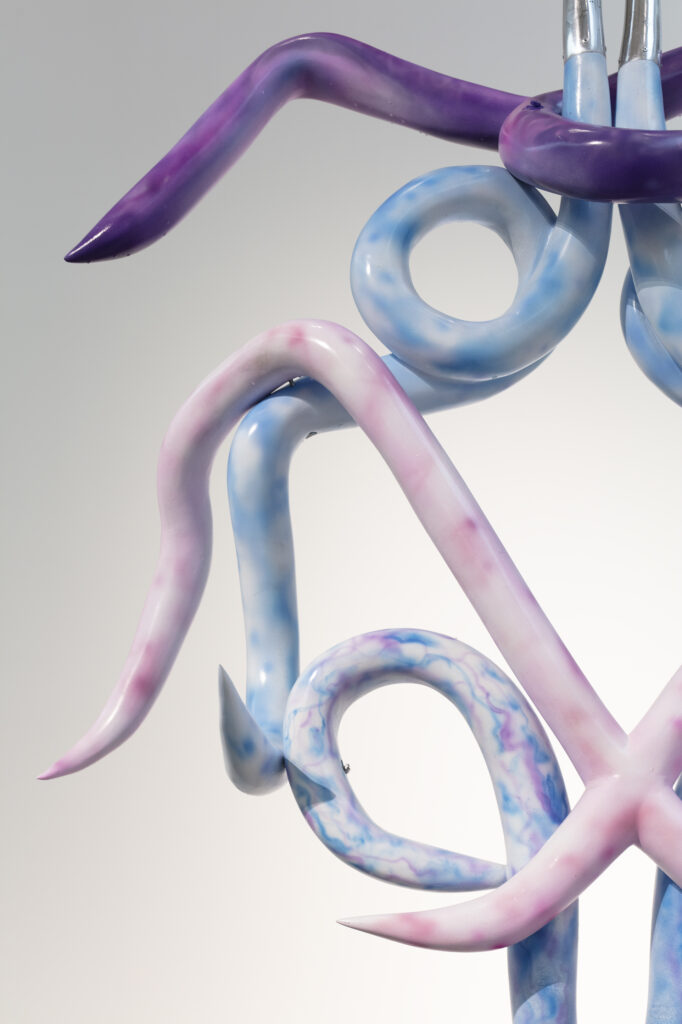

Because fetishism is a mechanism to objectify, a channel to become closer to something that might be terrifying because you do not understand it. In IUDUIUDUI, the two large-scale pieces are very purposefully made of parts and reconstituted into what is perceived as a single being, although anyone seeing it knows that it is made out of five, or in the case of the second work, nine pieces.

That comes back to the line of work that I started with while working with Antonella back in 2018 – exploring through ceramics, making these fragmented-yet-entire things that have autonomy and a proportional relationship to the body – although you don’t really know what they are.

This fetishism is a way of naming without knowing, it’s a port of entry. In terms of partitioning the body, I find it to be a beautiful human mechanism because it can act as a bridge. Fetishism is engrained in the Western mind, it makes the body understandable and approachable. It’s thought of as taboo, but it’s very common.

Photo: Zach Bowman, courtesy Von Ammon Co.

JMT: When first walking into the rooms where your pieces are being shown, there is a natural feeling of fear yet there’s an undeniable magnetism exuding from them. Their very presence is imposing. How did you achieve your distinctive style of sculpture?

KR: It was a conscious, strategic decision to move to sculpture. When I was working in costume, the ideas were all there but they were not being articulated. There is a psychotic collapse with clothes. Clothes are too close.

I literally thought of sculpture as a way of taking all of my clothes off and kind of throwing them into a pile that becomes petrified. This allowed critical distance, and it’s more familiar as an art object with hard materials.

The ceramics I make with textile molds – protean molds, molds that are malleable. They shape to the weight of the clay body. With this technique, everything came together nicely to fit into the discourse I had about artifice, and how it dictates the body itself – it’s not some sort of “add-on” thing.

I came from my own meandering in fashion theory and what is largely an extended independent study –, but many people are starting to think about the body in a different way because of current political climates that are advocating for rights of people that have been invisible to mainstream thought because they are different. There are a lot of artists situating themselves in post-humanism and more gender queering now. I’d like to think my work has implications for these topics, but on a more cognitive theoretical plane.

In the IUDUIUDUI sculptures, I could not use that same technique based on the scale, but it’s a translation of the visual language I’ve established through my previous work.

Photo: Kristin Reger, courtesy of Relaciones Publicas Art

JMT: You were talking a bit about your creative process, what does that look like for you?

KR: Well, there is a lot of self-torture. What I mean is trying things out, wasting time and money, questioning everything. Sculpture is the most significant for me, but it’s a feedback loop or a constant transmutation of almost any other medium- performance, textiles, painting. Then there’s digesting information. I read something and I become obsessed with it and talk to everyone about it. And there’s moving and feeling. The shapes I make are best described as ASMR suction sounds.

All of that is in the studio, the fun part. For these, I had to learn how to work with other people and chill my ego out. These pieces combine fiberglass, airbrush, 3D animations, bronze… I had to learn how to work in a team and it was a huge trip for me. The previous sculptures I’ve made are very visceral and intuitive.

JMT: And what drew you to ceramics then?

KR: It was just so analogous to all the problems of the body. It’s such a poetic metaphor, even a mirror, I would say, to the body.

It was great coming into ceramics not knowing shit. It gave me an irreverence and a freedom. For the IUDUIUDUI pieces, the first thing I did was make a collage. I took all the ceramics I had and put them into Photoshop and started to visualize a larger whole made of parts. It had to be big, it had to be phantasmagoric, it had to be mysterious. Something that is form-like but also a specter… it had to hang. I made the digital collages and then my boyfriend Matías Contreras saw them – “let’s make these into 3Ds”. Suddenly there was dimension, it was real. It was a transmutation of the previous ceramics, into a more complex but flat being of clear form, color and feeling, back into this 3D plane, and then figuring out how to make it into a large scale by working with a team of six people. There was also a structural engineering aspect to getting the pieces being a specific weight and having them hang from a tiny little point. That was Matías too, 100%.

The last series I did was in complete isolation, so it was nice to come out of that and learn how to work with others. It was the only way that it was possible. What helps me a lot is to constantly translate the medium I work with, from one to another. I’m not married to any, nor do I ever plan to be.

JMT: What’s behind your choice of location for the show?

KR: Antonella found the space, I was deep into production. We needed height, we wanted the pieces to float just above average human height. RP doesn’t have an official space. Anto had the idea that this building (Edificio Ermita) somehow belongs to everyone as a cultural landmark, and should be sort of public… the space is perfect for the spotlights, which complement the confrontational feeling we wanted. The sculptures don’t have a direct relationship to the space meaning they aren’t site-specific, although they can be thought of this way.

Photo: Fabián Valdes, courtesy of Relaciones Publicas Art

JMT: I totally see that. The rooms where the sculptures are used to be old movie theaters, and I think it adds to the element of performance in the pieces.

KR: We built on the idea of being specters, and that was intentional from the get-go. The two rooms have the capacity to host these alien beings. Anto pointed out there’s symmetry with the presentation of the work as well.

KR: Yeah, there are so many ideas and moments and people that play into the pieces that I get a little overwhelmed. I feel this sort of postpartum isolation where I think “I made that?”

There is this quote I love that talks about how etymologically the world larva is related to the word ghost in Latin. There’s a full-circle logic in this, relating the primordial or proto-being with the idea of whatever comes after death or beyond a body. My fundamental question is: what is a being? When, how, and why does something come into being? How is that understood as a body? This etymological reference, for me, encapsulates both the primordial abstract beginning of the before-form, of something like a worm and, that being related to what we think happens after we die, becoming a ghost or the continuation of an matterless or formless entity.

Then it gets crazier when I read the in-between usage of the word, the poet Horace used it to signal mask as well. So this really linked all the ideas I have now with what I was doing before. With how fabric can create a body. I bring this up in terms of the space because the people who work here say the building is haunted. Then there’s the fact that all of this information came from an article about ectoplasm, a phenomena from the beginning of the 20th century where the physical evidence of a supernatural matter emerging from the body is forged in photos.

Hosting in Ermita was genius on Antonella’s part because it made perfect sense with the pieces and people were curious about the space. We were already on the map and there is no reason to launch a permanent space these days – our support is human. The space is huge which worked for the protocols and made way more sense for the work than having some arbitrary white cube. I like to think we’re the badasses in town. We killed it and we don’t even have a “real” gallery.

JMT: What do you hope people take away from your work?

KR: Sculpture is automatically political because it takes up space. I want people to feel confronted. It’s not just a physical confrontation, it’s one with expectations. I don’t want people to know what it is. I don’t even want them to think they know. There is a cognitive apparatus at work in the pieces that is super simple: that they are symmetrical, and that is enough to be familiar, for the pieces to still be a mirror.

Symmetry is the force behind the validity of recognizing an animal, a person, as “normal”. The questions I am asking are a lot more fundamental but they have implications for gender, race, and class because it has to do with what someone recognizes as being valid or not. So what happens when you don’t know what the thing you are looking at is? What starts to happen? The recognition of whether something is or not is what decides whether it has rights or not. This is Bataille…

But these are not my questions, they are just sort of implicit in what is happening around us. I’m more zoomed out.

JMT: Do you have any idea of what sort of medium or projects you would like to dive into next?

KR: A while ago I was working with wax, latex, silicone, polyurethane… less permanent and more visceral materials. Latex has a problem that it starts to deteriorate after a year. It’s fun though and somehow more analogous or even truthful. On the other end, I want to keep pushing the scale, the “resplandor”, I guess the glare, a blinding or iridescent surface to as to further displace the limit of a body/entity. Here… I’m thinking glass. I want to continue exploring these mechanisms of cognition and fetishism and to make things that are weirdly sexy. All of that is fun, the language is there. But mostly, if they could float . . .

JMT: How do you see the art scene in Mexico evolving?

Everything here is fragile. There’s no romanticizing precarity.

I have to say I occupy a weird place here. I’ve been here for a while and studied here- there’s a commitment in that which made me into a cultural mutant. The perspective this has given me is probably more impactful elsewhere, and I’m starting to bridge my relationship to the city with projects in the US and Europe.

I can tell you what I think will, and what I think should happen, though. There’s a lot of hype about Mexico City. Like other big cities, it’s going to host more “digital nomads”, whether people like it or not. The smartest thing to do is orient newcomers toward helping to fortify the local activities, including the art scene.

Support small spaces and younger, local artists. Most are on Instagram, and there are many resources to find these people (shout out @relacionespublicas.art , DM to get to us, or look at @onda_mx and @terremoto_mx for lists). If you can buy, DO IT, and take risks on the lesser-known, on pieces that are meaningful and powerful to you. Show up and talk to people, whether you’re here for three days or 30 years. Community and resources – also on a more global scale – is what will help the hype grow into something that lasts for local people and for the next generation of artists.

Editorial Photos

Creative Director

Matías Contreras

Photographer

Julian Burgueño

Makeup

Valeria Salas

Styling

Shoes courtesy of Maison Margelia x Reebok

Clothing courtesy of Biali Obed Vara Saldivar

@ Reserva & Nayeli de Alba